Glamour, light, and revolution!

The Georgian Period

Usually described as lasting from 1714 when George I of Hanover inherited the British throne, through the reign of George II, III, IV and William IV, concluding with the ascent of Queen Victoria I in 1837. Lasting over a hundred years the period saw huge technological, economic, and social changes all of which had their impact on the fashions and jewellery of the time.

Georgian Excess

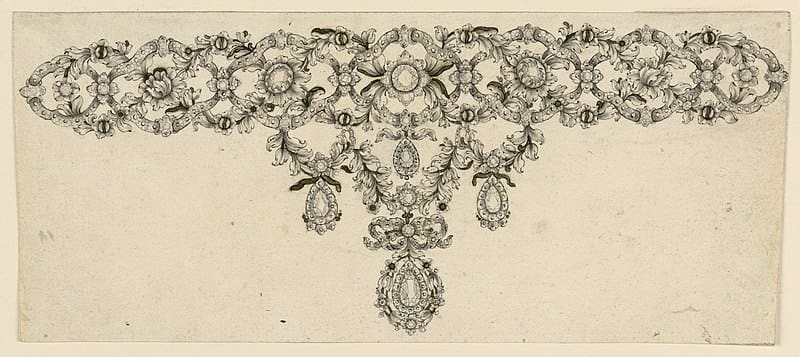

In the early Georgian period outward appearance and fashion became excessive, powdered wigs reached towering heights and dresses stretched sideways over wide hoops, and all of it was embellished with ornaments. French fashion and the rococo style dominated the decorative arts and jewellery was a riot of scrolls, bows, flowers, and feathers. The enormous canvas of the wig could be decorated with any number of jewels, ornaments, and swags of pearls. Huge three-tiered girandole earrings and choker necklaces often with large detachable pendants framed the face. Necklines plunged perilously low often with a large brooch in the form of a posy or nosegay nestled in the decolletage above tapering sets of bow brooches.

Balls, Operas, & Masquerades

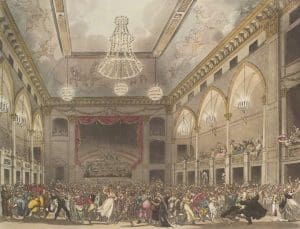

The flamboyantly extravagant dress was an opulent display of wealth and power and demonstrated a person’s right to be at the peak of society. Court functions increased as improvements in lighting allowed for larger numbers of society’s elite to congregate in the evenings. Elaborate dinners, balls, and masques were staged increasing the opportunities to see and been seen and the need to dress for the occasion.

Glitter and Sparkle

With their unmatched brilliance, diamonds were the perfect gems to glitter, flash, and sparkle in the improved illumination and were worn on the ears, décolletage, or neck to light the face. Previously the extreme rarity and limited ability to cut diamonds had restricted their use, but now technological developments in gem cutting had transformed diamonds from their uninspiring natural form, into facetted and sparkling objects of desire. Coinciding with the unprecedented quantity of diamonds arriving in Europe from the newly discovered Brazilian diamond deposits, diamonds fast became the supreme gem for evening wear.

To glitter more effectively in the new shimmering candlelight, the enamel and goldwork of previous eras was replaced by jewels made of gemstones set with as little metal as possible seen. However, behind the gems were set in a closed back which was lined with a thin bright metal foil that reflects the light back out through the gem adding brilliance.

Whilst diamonds and gemstones glittered in the flickering candlelight of evening events, through the day natural light flattered gleaming gold and rich enamels. For the first time there became a distinction between day and evening dress. Through the day in ‘undress’ (as opposed to evening ‘dress’) a more relaxed and natural look was favoured with gold and practical jewellery being worn. For a lady the first among these would be her chatelain which would hook to the waist and hold useful objects such as keys, sowing kits, and notepads, an object which remained popular well into the next century.

Social Changes

By the mid-18th century, the changes in trade and technologies which brought the luxuries and extravagances to the court also created a rich class of merchants and businessmen all eager to adopt the trappings of the nobility. Once a sign of power and rank, jewellery was now being worn by the simply rich, and it was being worn in great quantities. The demand for gems far exceeded the supply, and the pockets of even the best heeled was stretched in the effort to keep up with the latest extravagance.

Fortunately, Georgian innovators also produced high quality jewels made of ‘Strass’, a type of hard glass capable of being cut and polished to imitate gemstones, and pinchbeck, a gold-coloured metal alloy. Laboriously hand crafted to the same quality as the jewels they imitated, many of these pieces remained intact whilst their more expensive counterparts were taken to pieces for value of their parts. As with previous eras jewellery was often reworked into a new style as the component parts were too valuable to be replaced as quickly as fashion demanded. However, jewellery could also be used as portable wealth and could be taken to pieces to be ‘spent’, and this was especially true in the tumultuous times to come.